I understand the difference between the COVID-19, flu and cold.

What is a cold? A cold is a viral illness

The festival of Les Caramelles

It is the celebration of the resurrection of Jesus in heaven. It is a feast with rural origins. The Caramelles are popular songs performed by young people on Holy Saturday or Glory Sunday and extended the party until Easter Monday. The first recorded existence dates back to the 16th century in the rural areas of Catalonia.

Groups of young people went from house to house, singing and carrying a long pole with a basket on top to collect gifts. Normally eggs, sausages and other pork products or more rarely money, to then make a collective meal.

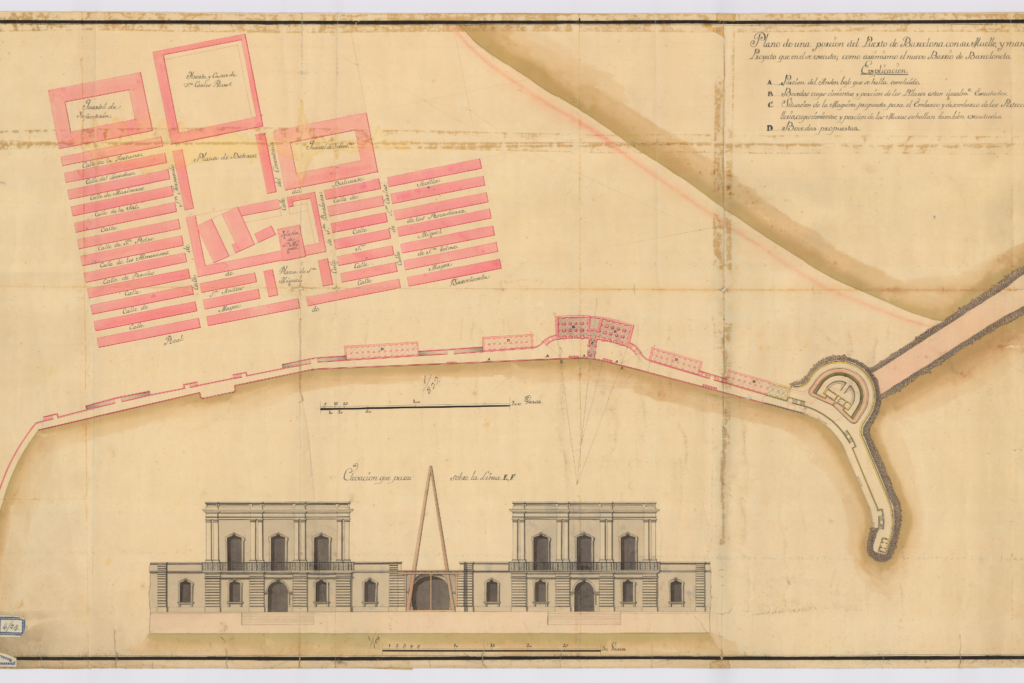

This rural tradition will be brought by the peasants to the cities when they went to work in the factories, taking a satirical and political tone. The oldest known information about Les Caramelles in Barcelona corresponds to the year 1766, but it seems that the first “colles” were not organized until the middle of the 19th century and did not become generalized until 1880.

The get-togethers.

One of the favourite customs of the inhabitants of Barcelona in the 19th and 20th centuries, on holidays, was to go on outings called “romerías” or “fontadas” on consecutive holidays, such as Easter.

They were excursions where a religious act was celebrated in the sanctuary, with the consequent lunch and peasant dance, among other entertainments.

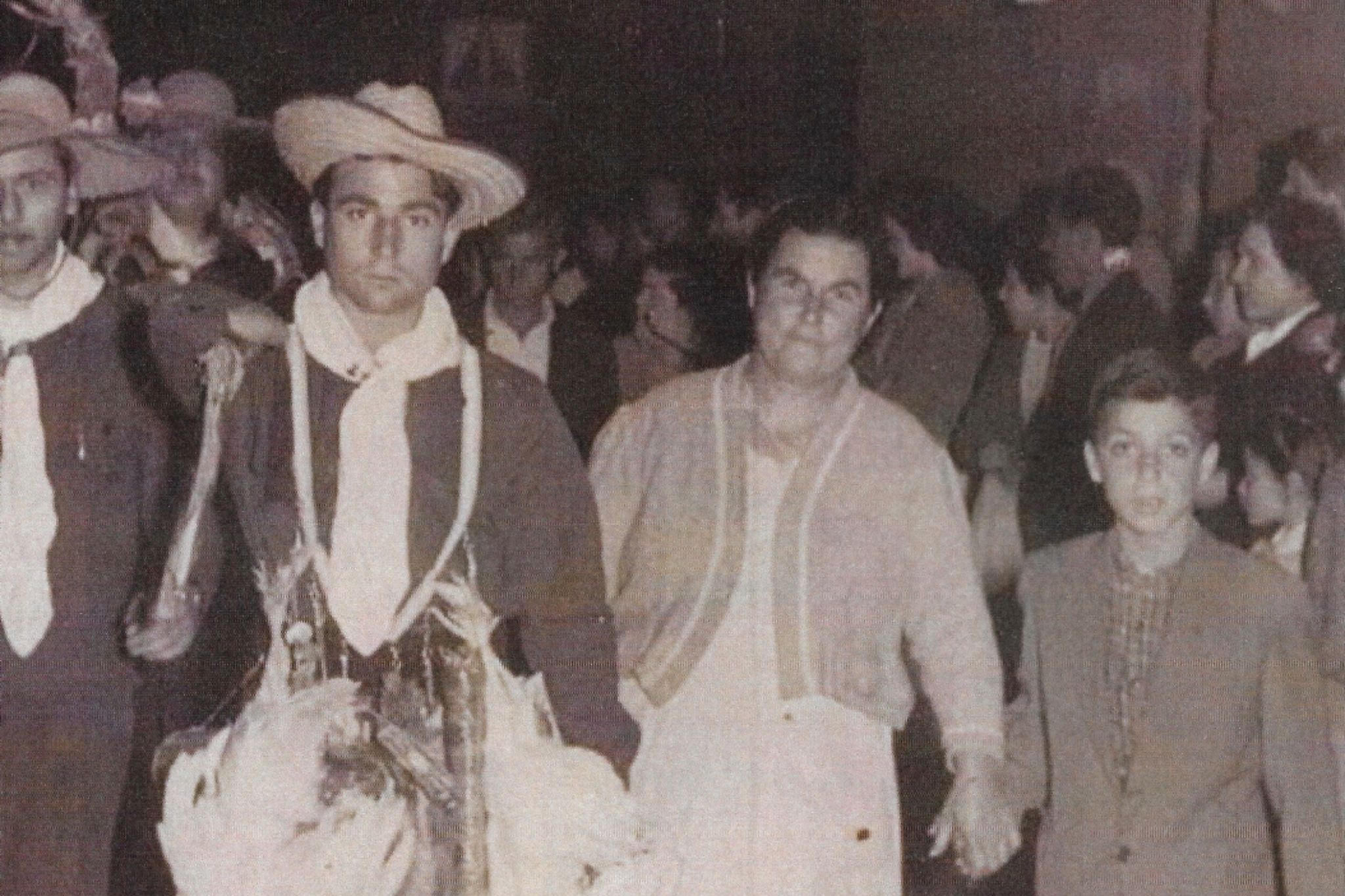

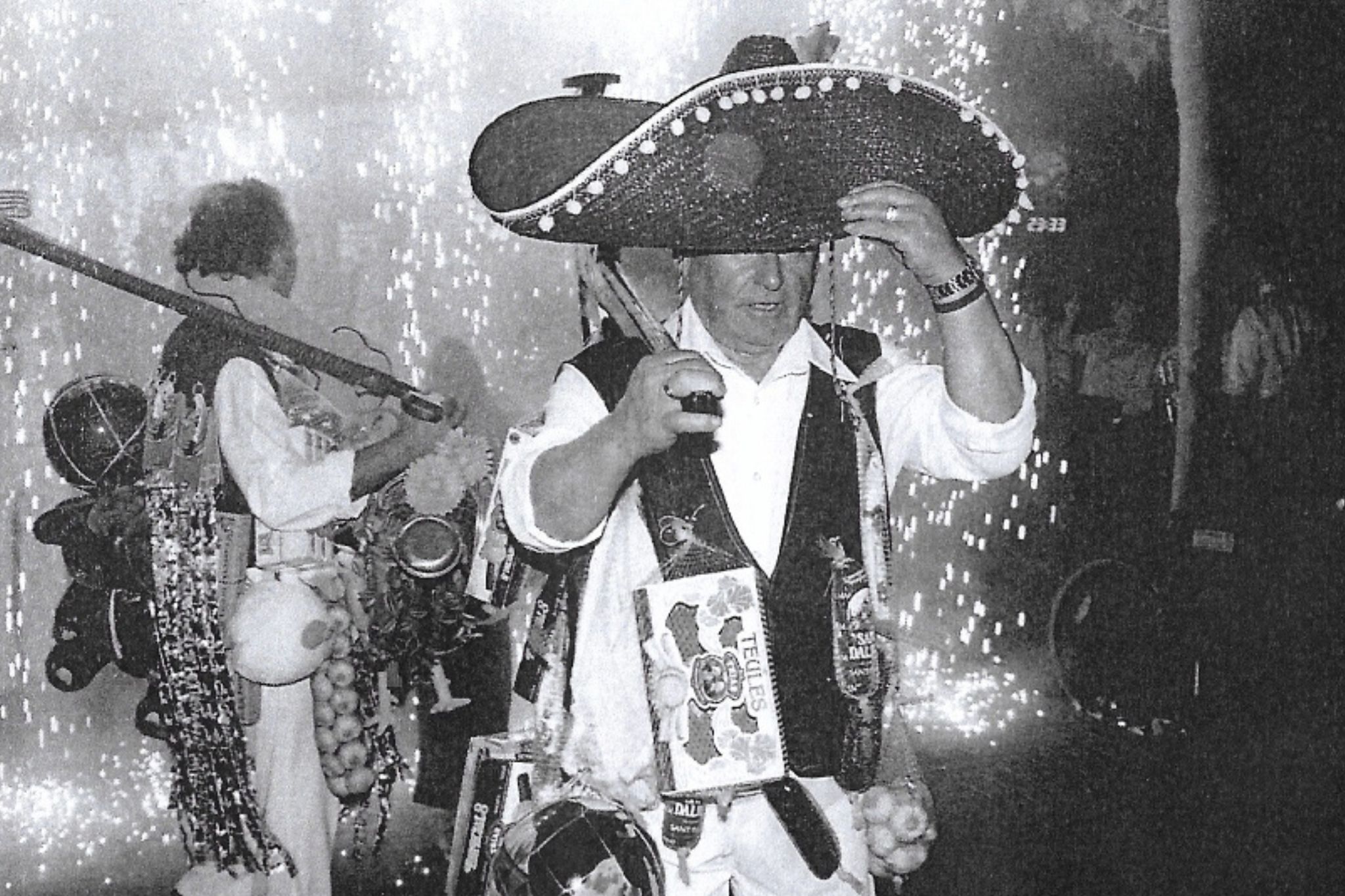

The working people gathered in groups of relatives, neighbours or coworkers. They rented stoves and cooking pots to cook the stew they brought with them, or they cooked rice and roasted meat on the grill or on the stone. They had a lot of fun and at sunset they returned home. Most of them went on foot. The groups of caramellaires also went out to make a fontada, the result of the produce of the food and the money they had collected by singing. They were lined up in two rows, the tallest and well planted in front. They carried, giant-sized wooden cooking utensils around their necks, like shotguns: spoons, forks, knives, with mortars, grills and other similar vessels, symbols of the culinary art. They set the pace to the musical rhythm.

The festival of San Muç o Mus

On the day of Easter Granada the meeting was celebrated in the hermitage of Sant Muç, saint patron of the chatos, located in the municipality of Rubí. There were several societies or groups. Some of them had more than 600 members. They wore a special uniform, consisting of a straw or soft felt hat, depending on the group, a colourful blouse, light-coloured cotton pants, pants, and espadrilles with veins (ribbons). The tallest, who were called gastadores, went in front and carried gigantic wooden spoons, forks, grills, etc., made of wood.

They walked all night, and headed for Rubí, at dawn. They carried popular and rustic instruments, with which they played a sort of popular march. They spent both days jumping, dancing, playing and singing. They returned to the city on Monday afternoon. Wives and children would greet them.

Later on, the Colla de l’Ancora appeared in Barceloneta. It was then followed by the Colla del Lliri from the neighbourhood of Santa Caterina Market. It might have been called so because they were located in the street of Flor de Lirio.

The Coros of Clavé

Josep Anselm Clavé (Barcelona 1824-1874) is a leading figure in the history of Catalonia as a Catalan politician, composer, and writer. In the midst of the industrialization process, he promoted associationism among the popular classes.

The culture promoted by the Cors de Clavé, in origin, was markedly popular and rooted in the territory, which strengthened the link between the popular classes and republicanism and Catalanism. As for the social context, we place it in the Barcelona of the mid-nineteenth century, the most industrialized city in the state.

He was born into a family in the Ribera neighbourhood. His father had a family carpentry business. At the age of six he lost the sight of one eye due to an infection, which contributed to his dropping out of school. Influenced by his mother’s sensitivity and taste for the arts, he dedicated himself, in an autodidactic way, to study music and poetry. Soon he began to hire himself out in different cafés in Barcelona as a guitarist. This introduced him to the world of the workers who spent their leisure time in taverns or bars, singing popular songs.

Since he was very young, he showed a left-wing and republican political affiliation, and was related to characters such as Narcís Monturiol and Abdó Terrades. All of them collaborated in the creation of the first communist newspaper in Catalonia. Between 1840 and 1843, he actively participated in the urban revolts that took place in Barcelona, for which he was arrested and imprisoned in the military fortress of Ciutadella.

When he returned to his activity as a musician in the cafés of Barcelona, he realized the acceptance and success of his compositions among the public. He proposed a more refined genre of songs than those that were fashionable in these environments and presented them as an alternative.

The contact with the working class and its needs will make Clavé see the possibility of bringing music, culture, nationalist sentiment, and class consciousness through the formation of coros. We can believe that Clavé’s associationism was a social and cultural revolution in the face of an extreme situation of helplessness of the popular classes.

He was gaining popularity and in 1845 he was asked to form and direct a modest orchestra society that would be called La Aurora, made up of about twenty men who played a wide variety of popular instruments (guitars, bandurrias, triangles, tambourines, etc.). This type of groups, such as fables or estudiantinas, proliferated between 1845 and 1849 in Barcelona.

From La Aurora, Clavé created a choral society, La Fraternidad, which would be the first in Spain, on February 2, 1850. Following the example of the Fraternity, similar choral groups soon began to form in Barcelona and neighbouring towns.

Following his imprisonment, in 1857, when Clavé was released, the society was renamed the Euterpe Choral Society, and the events were held in the Euterpe gardens, one of the parks that were opened near Paseo de Gracia and which disappeared in 1861. In 1863 the choral association, led by Clavé, had about eighty societies and almost three thousand singers – “all of them workers”- all over Catalonia.

Between 1860 and 1864 the federation of Euterpe Coros had a great echo and grouped thousands of singers and hundreds of musicians from all over the country. Parades were held along the main arteries of the city, with distinctive elements for the coros (uniforms, banners, etc.) and were convened in the cantadas that were offered in the bullring of Barceloneta (Toril) and in the Champs Elysees.

After 1880, an incalculable number of groups came out every year and invaded the city with the joy of their songs. They evolved into caramelles songs and many visited cafés, theatres and neighbourhood societies. This made them lead the songs to a field of criticism and satire, not always, certainly, in good taste. Some groups abandoned the barretina, which had characterized the first citizen caramelleros, to adopt a type of cap of their own special shape or colour that distinguished them from the singers of other groups. The distinctive cap was changed every year. They went down the street forming two rows in single file, presided over by the streetlamp, behind which were those who played. Those who carried the basket and the cart followed in last place. As they walked, they had a unique step.

The result of different traditions

With all this information we can conclude that the Coros of Barceloneta come from different traditions. To begin with, the party is very similar to the one they used to do for the festival of the meeting of Sant Muç. The way of dancing following a step, the utensils and the costumes show it.

Until very recently, the tradition of the Coros of Barceloneta, was to sing, performing choral acts. In the headquarters of each group, the men went to teach once or twice a week, studying music theory, music and popular songs. When they left, on Easter days in Granada, they usually performed in the towns where they visited. On their return, they carried food, kisses, chickens, and several other food products with them.

The oldest group is La Perla, formed in 1863. In the 1950s, the Agrupación Els Barretaires (1932) still published small booklets with the lyrics of their humorous songs. Several old gangs, such as L’Òstia or La Virolla, have disappeared over the years, but new ones have also been formed.

During the Civil War there were no coros and everything was clandestine, with arrests included, until 1951 when it was reactivated with El Ganxo, which was the first coro that dared to come out. The songs were satirical in tone with pasodoble music. Lyrics composed by characters such as Pincho or Julio Acosta.

The 90’s began with important novelties. The batucada was incorporated as a musical rhythm and the first women’s coro, La Sirena, appeared in 1990.

The Coros is a tradition that is prepared throughout the year and is enjoyed with devotion. Outsiders must maintain respect for the groups and remain as mere spectators, avoiding conflicts or interference. Only accredited participants can parade.

The event is a meeting point for the participants. 3 days to talk again and see friends with whom sometimes you only meet in the Coros.

You may also be interested in

What is a cold? A cold is a viral illness

The Christmas holidays are approaching and there are many things

A real institution in La Barceloneta. He was much more

More articles

The 4th edition of the benchmark event for the technology community took place on 12

Celebrating Christmas is one of Marina Puerto Viejo’s most cherished traditions. And this year, as

Next to a rubbish bin I’m going to find a very old Gladiator suitcase and

From 9 November to 10 February 2024. On the occasion of the celebration of the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _ga_2DMP7XMBDL | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| pll_language | 1 year | The pll _language cookie is used by Polylang to remember the language selected by the user when returning to the website, and also to get the language information when not available in another way. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Analytics" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 1 year | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Necessary" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to store the user consent for cookies in the category "Others". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to store the user consent for cookies in the category "Performance". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | 1 year | Records the default button state of the corresponding category & the status of CCPA. It works only in coordination with the primary cookie. |

| elementor | never | This cookie is used by the website's WordPress theme. It allows the website owner to implement or change the website's content in real-time. |