Therapy dogs

El Hospital del Mar y la Fundación Affinity ponen en

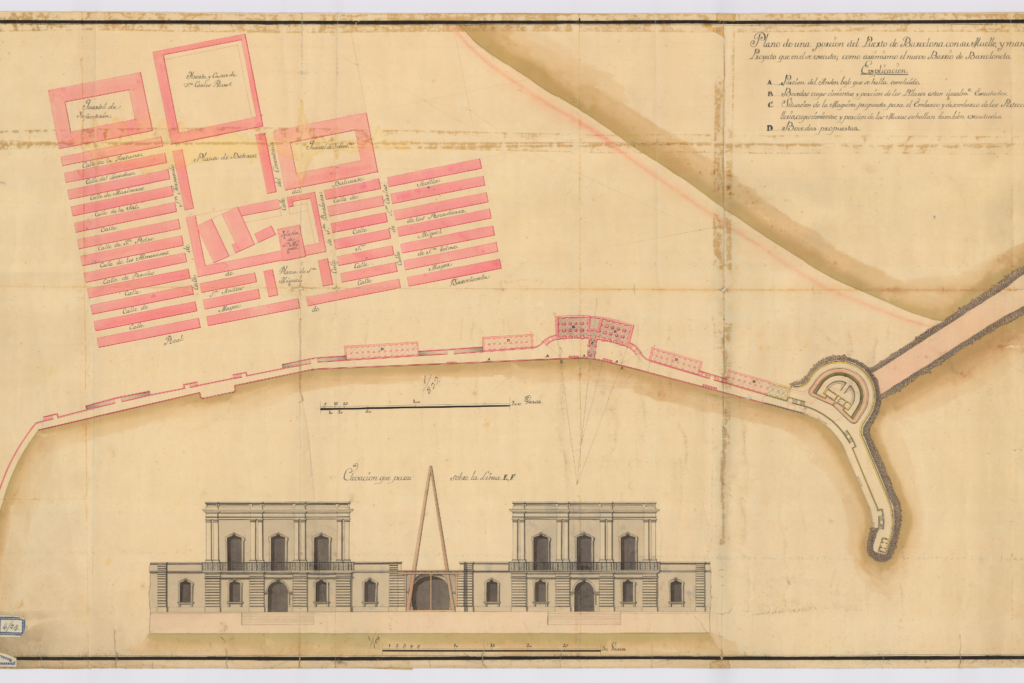

That is why the streets are a straight grid that came two hundred years before the invention of the Excel sheet. They were such serious people, with such an arithmetical sense of life, that they forgot to open spaces for playgrounds, gardens and other useless things. They also forgot that Barceloneta is a piece of beach laid by the sea, that nothing is firm and that everything can be swallowed by the sand.

In the middle of the neighbourhood, the engineers placed a huge cavalry barracks of San Carlos because everything was well controlled: 1,200 soldiers, as many horses, cannons … So heavy was the weaponry and the military, that it sank in the sand of the times. After a few decades, there was no trace of it and after its disappearance in 1930, a large square was finally opened, named after Francisco Magriñá, who was the politician who allowed the neighbourhood to have its sewage system.

People grabbed the square with enthusiasm. However, the republican square where the unemployed liked to go to sunbathe so much also disappeared and in 1951 a school with its playground appeared. The square was renamed Plaza del Poeta Boscán, who was one of those poets who did not bother anyone because he had been dead for five hundred years and no one would make protest songs with his lyrics.

The school was ugly, it was a grey mass with a disproportionately large central body, as if you put the head of a giraffe on a mule, but it was there, where many of us learned that two and two equals four. And we learned what life was.

The school playground was used for everything. In the afternoons and weekends it was a playground for the whole neighbourhood. Since we have always been fond of shortcuts here, this square in front of the school was called “Repla”. My macaronic career as a street soccer goalkeeper began (and ended) there. It was the only playing field in the whole neighbourhood, where three or four games were played at the same time and in each goal, there were three or four goalkeepers from different games. It was chaotic, but it was fun. Sometimes you were watching your own team and the other team’s goalkeepers would hit you in the face with a ball. It hurt, but it was tough.

The Colegio Virgen del Mar was a place full of mysteries. Nobody knew what was upstairs, where the mechanism of the huge clock on the facade was. It was said that the clockmaker was a hidden red, that when the civil guard came to inspect, he got between the gears and that is why sometimes the handle of the hours was his own arm. It was also a mystery that one September the crucifixes and the photos of that half bald man whose name we could not say had disappeared from the walls, and the portraits of a man who was said to be a king, although we could not see his crown, appeared.

This bustling Repla that buzzed with life and the school of thousands of tons, were also swallowed up by this square where nothing is permanent. One day I returned to my school and it was gone. There were only a few photos left for the memory in the bars of the square, in the Cova Fumada and in the Bar l’ Electricitat. I felt indignation because some tricksters had turned a school and a popular playground into some bar terraces. Then I laughed. It was that square in the middle of the neighbourhood that did not allow itself to be dominated. These terraces of bars that we see now, will also disappear one day, and when someone starts missing them we will have to remind them that Barceloneta is sand.

Antonio Iturbe is a journalist, a university professor, a writer and, to top it off, he is from Barceloneta.

You may also be interested in

El Hospital del Mar y la Fundación Affinity ponen en

The only Pilates Reformer studio in the maritime area between

It would be very difficult to find a scenario as

More articles

The 4th edition of the benchmark event for the technology community took place on 12

Celebrating Christmas is one of Marina Puerto Viejo’s most cherished traditions. And this year, as

Next to a rubbish bin I’m going to find a very old Gladiator suitcase and

From 9 November to 10 February 2024. On the occasion of the celebration of the

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _ga_2DMP7XMBDL | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| pll_language | 1 year | The pll _language cookie is used by Polylang to remember the language selected by the user when returning to the website, and also to get the language information when not available in another way. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Analytics" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 1 year | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Necessary" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to store the user consent for cookies in the category "Others". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to store the user consent for cookies in the category "Performance". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | 1 year | Records the default button state of the corresponding category & the status of CCPA. It works only in coordination with the primary cookie. |

| elementor | never | This cookie is used by the website's WordPress theme. It allows the website owner to implement or change the website's content in real-time. |