70 years of the Barceloneta Merchants’ and Industrialists’ Association

Background Throughout its history, Barceloneta has always been very active

Many times during the last few years I had contemplated the image of that man – today dejected – with a sheet of paper in his hand and a distracted look that longed for the reading of that letter to last as long as possible, imitating a child who enjoys a sweet treat and hopes that the pleasure will be extended; a pleasure, however, that day I was going to see it, transformed into pain. Manuel, after reading the letters, in a ritual way, always stood up, shook his head in farewell and left without saying a word. That day, however, I would shudder like never before. Manuel would read and re-read the letter, making pauses, during which, his gaze would get lost in the horizon.

Finally, he looked at me and said with tears in his eyes: – I became a great-grandfather. In the 10 years that Manuel had come to the workshop to collect that correspondence, he had never commented on the contents. I could tell from the stamp I had seen that the letters came from Buenos Aires. For years they kept arriving monthly, and although I did not know exactly who sent them, it was very clear to me, what the reason for this periodic communication with the New World was.

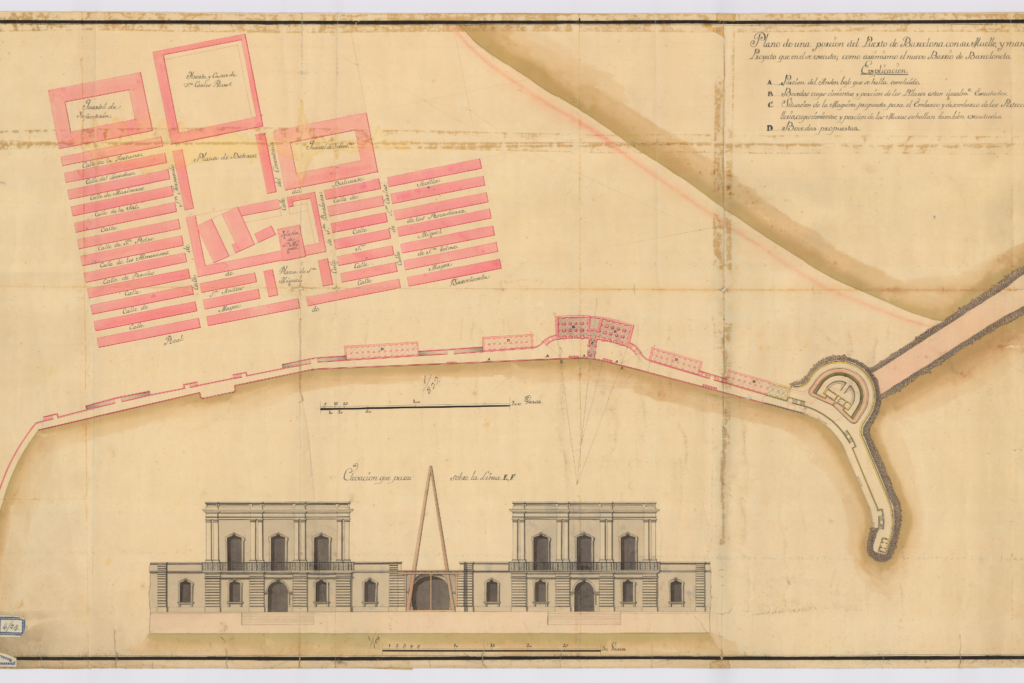

At the beginning of the 20th century, the port of Barcelona was in full expansion. Goods were piling up at the docks while ships were waiting to be unloaded and loaded and wagons were beginning to distribute cargo throughout the city. In the port there were the pailebots, the old “Libertis” with their crane-like loading booms, all kinds of steamships and sailing ships, as well as those anchored in the bay outside the shelter of the breakwater that was beginning to grow, and where the large cargo ships sought shelter from a possible storm.

At that time, loading and unloading was done by hand, or rather on the “backs” of the stevedores, rough men with enormous strength, who, sometimes helped by cranes as rudimentary as themselves, did a job for which they are still admired to this day.

The transport arrived and departed from the docks continuously. The carts pulled by old Percheron horses that slowly came from the sawmills of Horta, Badalona, La Conrería or San Andrés never stopped going in and out of the port transporting a single six-meter-long log, one meter in diameter and up to five hundred kilos in weight. It took the whole day to make the trip: loading, going down to the port, unloading and returning to the sawmill. Other wagons carried barrels of wine, oil, olives and other goods that were not going to the New World.

The thing is that between loading and unloading a merchant ship that made the route to South America could take from 12 to 15 days, 20 or 25 days to cross the Atlantic Ocean and about 15 days more to return to load and unload at the place of destination. The sailors took advantage of these fortnights to relax and see their families, foreseeing the long time they would spend at sea without seeing them.

However, when the ships docked at the ports of ultra-sea, in spite of crew as well as the shipping company being all Spanish, many seafarers carried by these long separations and the time abroad had formed another family in the country of destination and had kept secret the existence of this other family in the country of origin, as a confirmation of the saying that sailors have “a girlfriend in every port”.

Times were different and it was not too complicated to lead this double life. Both families were able to support themselves with smuggling, which allowed them to bring products that could not be found here and that were highly valued on the black market, something that generated an extra income that complemented the salary of these “transoceanic bigamists”.

But nothing lasts forever, Barceloneta was one of those ports that evolved day after day. Pushed by transformations that did not stop taking place and dragging it towards unpredictable changes to which its inhabitants tried to get used to with resignation. Still, no one was prepared for what was coming.

First it was a honk of horn, loud, long, pitying as the whining of a mortally wounded animal. The cause of the moaning was precisely the imminent end of an era, a way of life and a way of working. All it took was one honk of the horn and our world changed in the blink of an eye. Then we experienced.

A truck, gasoline engine, wooden body, capacity to transport five logs and the possibility of making five round trips a day. The fifteen days of loading and unloading became three or four at the most. A whole service industry that depended on traditional transport understood that its days were numbered: stables, veterinarians, wagon makers, drivers, farmers, feed manufacturers, blacksmiths, as well as utensils such as tools, bridles, implements and hides, in other words, a whole host of trades and utensils disappeared overnight.

Everyone predicted the end of the world, a very serious crisis that would leave 60% of the working class unemployed.

But time proved them wrong, the automobile industry gave work to half the world, although it did change the lives of those men with two families, of whom there were hundreds only in Spain. Since the ships only stayed between three and five days in port, the sailors had to choose a base and choose with which family they wanted to spend the month of rest they were entitled to after each voyage.

Most of them chose Barcelona because in addition to wife and children they also had parents, siblings and the rest of the family. It was very hard, especially when they had to retire, and they rightfully left all hope of seeing their family on the other side of the Atlantic. And it was this new situation that I was going to be an associate of.

A few retired sailors from Barceloneta asked me if they could send their mail to my workshop. I could not refuse, those men had recommended me to the companies in which they had worked so that I would take care of the work on their ships and that they would not order them in other workshops outside Barcelona. So I accepted. For years I became the post office box for the old sailors who would stop by the workshop and sit on the stool at the entrance where we would have a chat. Sometimes, two or three would coincide and chat with each other and enrich my mind and soul with stories of countries I knew nothing about. Little by little they all disappeared, some died, others left home with the excuse of going to buy tobacco and never came back, the latter were those who had chosen the wrong place to stay and wanted to make amends for their mistake.

When this happened there was always a letter that did not get an answer. After a while, the second letter would arrive, but they would no longer receive them. Then, I would burn them without opening them out of respect; after all, no one would claim them.

That day, Manuel seemed to stumble around the corner of Proclamation Street, staggering as if he were drunk; I knew it wasn’t that and I thought that the next letter would have no answer. The first one arrived and thirty days later the second one.

I went to his house a couple of times; the last month he had not been out of bed. I carried the two letters in my pocket and tried to show him the envelopes slyly, but he kept shaking his head from side to side in denial, which is why I put them away again, hoping he would recover, even though I knew that this old sailor who had spent half his life wondering if he had made the right choice would never again sit on that stool, which I would burn when I opened the shop the next day.

There will be no horse-drawn carriages at Manuel’s funeral; the coffin will be taken from the Sancho de Avila morgue to the Montjuïc incinerator in a modern “Mercedes”. I will give my condolences to the widow – inseparable companion of the old sailor – who in her eighty-seven years could not wait to be reunited with her loved one, oblivious – I believe – to the fact that, if they had performed an autopsy on that man, they would have discovered that he had a broken heart.

When I squeezed the hand of his only son to give him comfort, I put the two letters in the pocket of his jacket. -That’s from your father, don’t open them now, better when you’re alone. He will make a surprised face. He never understood why, being a man of few words, his father spent so many hours in my workshop, but he would never dare to ask him.

I did not see Benito, Manuel’s son, until two years later. He came to see me after a business trip; he was a mining engineer and traveled everywhere.

-He always talked about you. Sometimes I was jealous because he gave a lot of importance to your work and none to mine. I will find all the letters and when I read them, I will understand everything. I lived with my father for fifty years and now I realize that I didn’t know him, that I knew almost nothing about him.

-He always talked to me about his son. He was very proud of you and your work. I assure you.

We went to eat together at Pepita’s bar in Andrea Doria street, near the workshop, we were talking for about two hours and then we said goodbye with a big hug; with our eyes full of tears and our voice strangled, in so much pain that we weren’t even able to say “Goodbye”.

You may also be interested in

Background Throughout its history, Barceloneta has always been very active

From 9 November to 10 February 2024. On the occasion

A real institution in La Barceloneta. He was much more

More articles

The 4th edition of the benchmark event for the technology community took place on 12

Celebrating Christmas is one of Marina Puerto Viejo’s most cherished traditions. And this year, as

Next to a rubbish bin I’m going to find a very old Gladiator suitcase and

The basket of “La Garba”, raffle on the 5th of January at 12h. Days of

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _ga_2DMP7XMBDL | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| pll_language | 1 year | The pll _language cookie is used by Polylang to remember the language selected by the user when returning to the website, and also to get the language information when not available in another way. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Analytics" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 1 year | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Necessary" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to store the user consent for cookies in the category "Others". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to store the user consent for cookies in the category "Performance". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | 1 year | Records the default button state of the corresponding category & the status of CCPA. It works only in coordination with the primary cookie. |

| elementor | never | This cookie is used by the website's WordPress theme. It allows the website owner to implement or change the website's content in real-time. |