When running water had not yet reached the houses, you still had to meet the needs of drinking, cooking, cleaning, washing and, of course, ‘doing your business’. The older ones will still remember how they managed to get hold of drinking water and also how to get rid of the sewage.

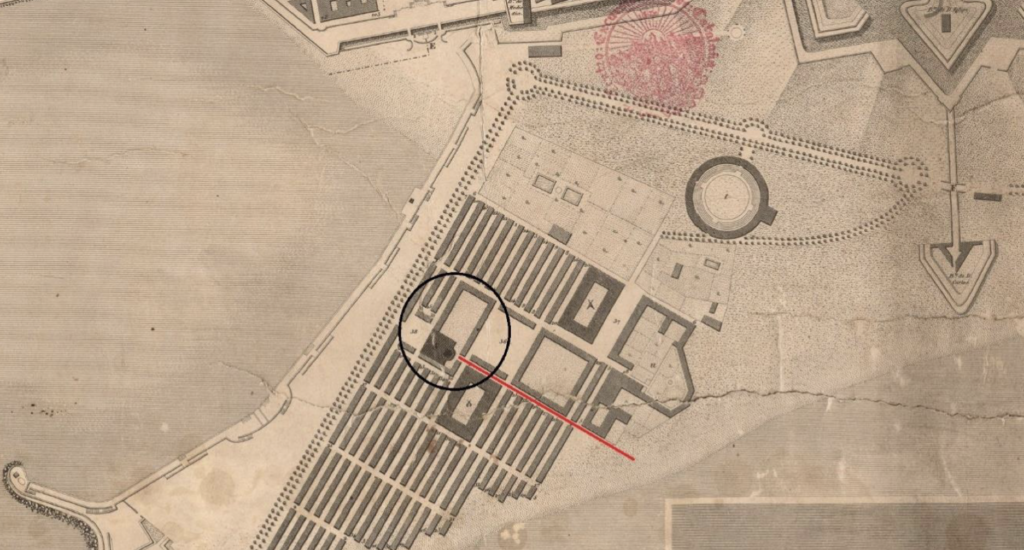

Barceloneta is a neighbourhood that was designed all at once. And the ways of getting drinking water and getting rid of sewage was another thing to take into account. Thus, a whole series of pipes were planned for the public fountains, the sewage system and for each of the houses, which had to have their own well and an irrigation canal.

Guitert de Cubas, in his book, explains the vision of the birth of Barceloneta: ‘Once the land was levelled, for which it was necessary to do an immense amount of work, since mountains of sand had to be levelled, the beach was swarming with workers, opening wells and foundations with fastening’. As can be seen, the wells were essential for extracting the water used on a daily basis, being the only way for the inhabitants to obtain it, together with the public fountains, as running water had not yet reached the houses. This did not arrive until 1872, at that time, the City Council granted a concession to the company Grappin, Calvet y Arce, which was responsible for supplying drinking water to the houses in the neighbourhood. But this does not mean that all the houses got the desired drinking water. Around 1973, a large part of the houses were still supplied by a tank that was filled up at night and was the source of water that could be used during the day for the whole area, something that also, not often, generated conflicts when someone used more water than necessary.

Public wells, private wells

The first public well we know of is the San Elmo well, located next to the Portal de Mar, where the Paseo Nacional (Paseo Juan de Borbón for outsiders) and Doctor Aguader now meet. Among the sailors there was a belief that its water was blessed and that is why they watered their boats with its water, on the day of the saint’s ephemeris. But as early as 1820, Guitert de Cubas tells us that in its place there was a fountain with three taps.

It seems that over time, the public wells were replaced by fountains due to the hygiene and health problems that they entailed because of filtrations with other water from the subsoil, rainwater and dead wells. We believe that these wells were basically supplied by rainwater, which was often contaminated by the excrement from the cowsheds and stables of the businesses.

In October 1884, La Vanguardia published the following piece of news: ‘it was also agreed, at the proposal of the health commission, to sanitise the wells by pouring ferrous sulphate, a powerful disinfectant, into them, a measure which could be extended to those of Barcelona, authorising the mayor to do so, so that he could arrange whatever he saw fit’. Hygienist trends had arrived and the City Council took measures by creating ordinances that sought to facilitate the circulation of air and water, increase the number of fountains, renew the sewers and pave and water the streets of the neighbourhood.

The growth in height and the partitioning of the interior of the buildings meant that the private wells, which were originally for a single building, became shared by two buildings and were located in the middle of the partition. At the same time, these wells also grew in height to reach the new raised flats and the new neighbours were able to draw water from the communal wells by means of a pulley with a rope and a bucket. The private wells, most of them also in a state of unhealthiness and with putrid water coming from the subsoil and rain, slowly disappeared, but like any change, it cost a lot.

In January 1919, in the memoirs of the Barceloneta Property Owners’ Association, there is a complaint filed against the order to close the wells in the houses. This regulation threatened with fines of 500 ptas. in the event of non-compliance with the resolution, which took the neighbours by surprise. The owners’ association claimed, in order to avoid closure, that the water extracted was only used for cleaning work, but the Municipal Hygiene Commission had the wells in its sights as a possible source of diseases such as typhus. Despite the repeated problems, there is evidence that around 800 wells were still open at this time.

In Barceloneta, space is important inside the houses and, therefore, no m² can be lost, so these wells did not disappear, but were transformed into small courtyards of light, where there were the vents of the kitchens and communal areas. But as we Barcelonetinos are very ingenious when it comes to putting things in small spaces (there is a Swedish furniture company that should learn a lot from us), some neighbours went even further and put some hanging shelves to create a small pantry or place to store those utensils that didn’t fit in the house. With the arrival of city gas, it was the ideal place to put the heater, and one woman testifies to having even seen a shower installed.

The communal wells, a hole to relieve oneself

If the wells were one more element in the planning of the houses, the same happened with the communal wells that had to be located at the entrance of the houses, with their small vent facing the street, to be connected to the sewers or next to the well of the building to have an air outlet.

Thy were a hole in the middle of a kind of step, to give height and sit, covered with wood, and used for relieving oneself. Since there was no running water to flush the excrement down, if it wasn’t flushed down immediately, a bucket full of water could remain indefinitely, with the resulting odors. Either you collected a lot of water from the fountain to use for different services, or you had to go down constantly. The dimensions of the wells were tiny, and it only included the space of the hole and enough space to fit your legs and close the door.

The “revolutionary” toilets arrive

Innovations from the continent led to the development of communal toilets, which were revolutionary inventions like toilets. Once again, the people of Barcelona used their ingenuity to install a toilet and a cistern in the communal space. The problem depended on whether you couldt fit inside the tiny space. The exercise of pulling up your underwear with the door closed was similar to what the world’s greatest contortionist could do. And as you might have guessed, there was no choice but to relieve yourself with the door open, provided you weren’t lucky enough to receive those unexpected visitors who never left.

And if the thing was complicated, we can complicate it even more, and if in the houses of the Eixample people used to make toilets with a shower, so did we. The thing was easy, taking advantage of the running water pipe that normally went up the well, a tap was installed with a shower hose and a water outlet was made to the ground taking advantage of the toilet pipe, which then had two functions: to defecate and to sit on when you took a shower. It couldn’t have been more comfortable!

And nobody could beat us for cleanliness, because before the installation of the shower, the body was cleaned in the kitchen sink or in a basin. Many neighbours used to go to the club of which they were members, using it as an adjunct or expansion of their home. An urban legend in the neighbourhood says that the Barceloneta clubs were created so that the residents of the neighbourhood could go to take a shower and relieve themselves. Who hasn’t used the phrase ‘I’m going to take a shower at the club’?

The curious origin and evolution of toilet paper

Our ancestors used various items for intimate cleansing, from straw, grass, stones, pieces of clothing or even sponges. The first revolution in the change of cleaning, however, was thanks to the appearance of the daily press from the 18th century onwards, because its sheets were very useful for cleaning after reading. Grandmothers used to cut them into small sheets and hook them, usually on a hook or a nail, placed next to the toilet,to be used when necessary, tearing them off one sheet at a time.

It wasn’t until the end of the Second World War that the second and definitive revolution took place with the popularisation of toilet rolls. In Catalonia, and the rest of Spain, the famous toilet paper that everyone knew as El Elefante, manufactured by Papelera Española, was launched on the market, wrapped in yellow cellophane. It is curious because at no time did it say, on the label, that it was so called, there was only the drawing of the animal and the legend of 400 sheets, which was supposed to be the number of uses, but as the paper was not perforated, it was not possible to know if this was true. It was a light brown paper with two sides: one matte and with a scratchy surface and the other satin, which prevented absorption. Fortunately, things have evolved favourably and now we have a fluffy and smooth paper.