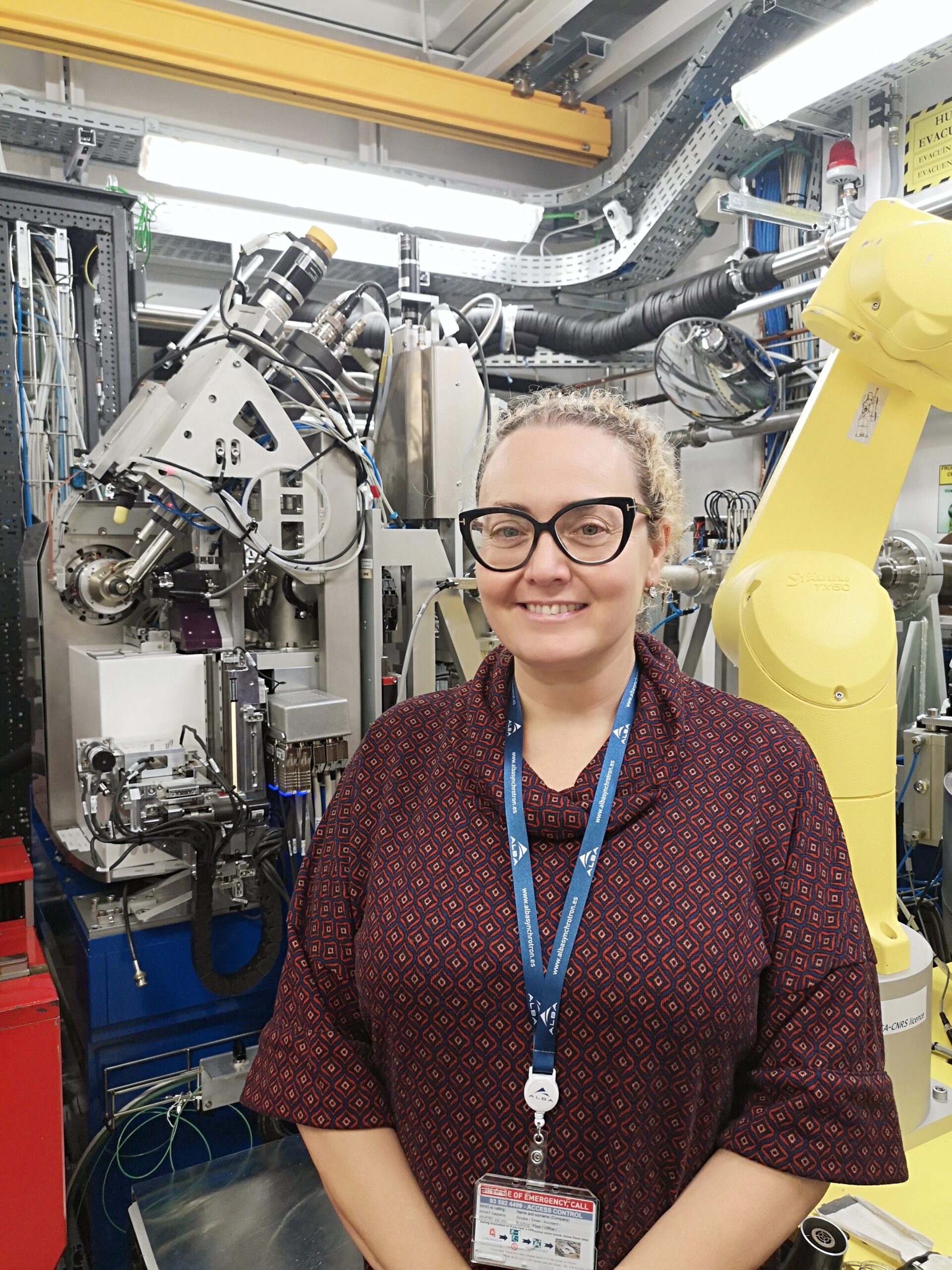

Eva Estébanez-Perpiñá

“We are working to fight prostate cancer”

She does not boast of having two degrees which she did at the same time, nor of being an internationally recognized scientist, nor of leading a research group to, among other projects, fight that damned prostate cancer that worries those of us who are already 50 years old so much. She boasts of teaching a Nobel Prize winner how to make Catalan cream and, above all, she boasts of being from Barceloneta. She is Eva, the daughter of Rosalía and José Luis Perpiñá

1- Ever since she was a little girl, she knew that she would study nature, although she did not yet know that it was going to be called Biology and Biochemistry.

I have always loved taking care of plants. I was attracted to nature. When I was 5 or 6 years old, I told my mother that what I wanted was to have a flower shop. To have plants and flowers but above all, to study them.

2- Student at the “ Virgen del Mar” College and at the “Joan Salvat-Papasseït” High School, always in Barceloneta.

My parents were very clear that we had to go to school here and to feel this neighbourhood atmosphere. Those were very happy years. I loved the Virgen del Mar and I remember that building very fondly.

I especially remember 3 teachers who left a mark on me: Imma, Esperanza and Santiago -Salvi-. I was a very curious child, and they knew how to stimulate that curiosity. When I was sick with asthma and it was impossible for me to attend class for months, they took care of me so that I could follow the course. I will never forget it.

3- University (UAB) arrives and, not happy with studying a difficult career, you study two (Biochemistry and Psychology) plus some medicine subjects.

I was sure I wanted to do biology, but thanks to the psychology classes I received at COU I thought I also wanted to know the biological basis of behaviour. In fact, I started with psychology first and the second year I studied both in parallel. They might seem far apart, but I think that behaviour also has an important biological part. Yes, those were crazy years. Years of studying a lot and living the stress of exam time multiplied by two, but I would do it all over again.

4- Then it was time to specialise and do your doctoral thesis. So, you go and rub shoulders with a Nobel Prize winner. Why should we settle for less, right?

It was a coincidence. I insisted to my career tutor that I wanted to go abroad and at that time, without internet, you didn’t know much about possible destinations and opportunities. Until he told me about the possibility of going to Germany in the Robert Huber group. I said yes, but I didn’t even know who he was. I told a colleague about the possibility and he asked me in surprise: “but, do you know who he is? He is a Nobel Prize winner!” Then I was aware of the implication that this would have on my professional future. I went with my colleague Marta, and they gave us an initial contract of 3 months. We must have convinced him because he renewed it with a 3-year contract. Undoubtedly, my tutor at the Universidad Autónoma saw very clearly where I would fit in.

5- And within Biochemistry, your specialty is all about molecules.

I specialize in Structural Biology and Biochemistry-Biophysics. I study proteins, which are the workers of our cells, in charge of performing different functions. We could say that my passion is molecular. I like to see them in atomic detail. I go to the Cerdanyola Synchrotron, which allows us to study them in much closer proximity to see what shape they have and how they work, and then to think about how we will design drugs for different diseases.

6- An example of the drugs you design?

We are working to fight prostate cancer. This is a cancer that affects 1 in 6 men over the age of 50. We are looking for new drugs that can make it chronic, thus slowing down its development and allowing the patient to survive for a long time.

7- Well, on my behalf and on behalf of all those of my generation, thank you.

But the most important thing is prevention. Don’t skip your check-ups and have regular PSA tests ordered by your urologist. They can save your life.

8- You developed a large part of your career outside our borders, is there no future for science here?

I didn’t leave because I didn’t have a future; I had opportunities here. I think we have a future here and, above all, we have an impressive potential that, yes, is not always taken care of as it deserves. Neither in terms of resources nor in terms of salaries. But I liked to travel, and I wanted to see how people work in other countries and then come back.

9- I thought you scientists never leave the laboratory.

We spend many hours in the lab, logically. But I think the work of a scientist requires a lot of traveling around the world. To train ourselves, attend conferences, keep up to date with new techniques, meet other professionals and exchange experiences.

10- Is science a man's world?

Unfortunately, in some positions it still is. During the careers, at university, there are many girls, but as you go up the professional ladder, the female presence decreases. There comes a time when many women have to decide whether or not to become mothers. Some choose to delay motherhood, as it was in my case, but many decide to give up motherhood for their profession. But – let’s call them – “bosses bosses” are usually men. I’m sorry, but that’s the way it is.

11- But you've done it. You are a mother.

I had my daughter Milena just when I started my independent research group. Reconciling the two facets was difficult. Besides, I did not stop teaching at the university. In other words, I combined research, teaching, and motherhood. I breastfed, went to lectures and gave a new feeding before entering the laboratory. But, once again, my great help was my parents. Without that family support it would have been impossible.

12- Do you also teach?

I love it. I teach about 250 hours a year. Dealing with the students is very enriching for me and forces me to be constantly training. Afterwards, some of these students become colleagues.

13- Jens, your partner, is also a renowned scientist, do you only watch Discovery Science at home or have you dared, for example, to watch “Sálvame Deluxe” (Society Tv program)?

Saturday´s Deluxe is perhaps too hard, but I have put Torrente on. An amazing character for a German like Jens. But at home we watch a lot of Spanish movies and series of all kinds, we especially liked Breaking Bad, we are also fans of Sheldon Cooper, and we like science fiction. But yes, we do talk about science at home. We are two very geeky scientists and it’s hard to disconnect 100%.

14- Robert Huber, your partner Jens... Have we been germanised Eva?

Or have I Catalanized them? Jens is a Barcelona enthusiast. In fact, he first got a place at the IRB, Institut de Recerca Biomèdica, to come back here. You can’t imagine how fond I have made Huber and other colleagues from Germany, America and different parts of the world, of “pa amb tomàquet” or “crema catalana”. Some of them already make it better than me.

15- Let's go back to where you came from, what is the neighbourhood for you?

I think you always carry your neighbourhood inside you. Your origin, your people. When you are far away you miss it a lot, above all your family and your former environment. This was especially true before, as there was no WhatsApp or video calls. At the beginning, in Germany, we communicated by fax. I have always tried to adapt to the place where I was, to live it and make it a little bit my own.

But yes, the neighbourhood is my home. For me it’s very nice to meet people and to be known. I like the fact that I am not anonymous, that I am recognized as “the daughter of Rosalía and José Luis Perpiñá”.

It all started at the Virgen del Mar

At the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) she was able to combine Biochemistry and Psychology, and Medicine subjects. She specialized in Structural Biology and Biochemistry-Biophysics during her PhD at the Max-Planck-Institut for Biochemistry in Munich, Germany, under the direction of the prestigious scientist Prof. Robert Huber (Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1988).

Later on, it was Vancouver (Canada) and in the laboratory of Prof. Robert J. Fletterick at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Finally, she started her independent laboratory thanks to a Ramon y Cajal grant from the Spanish Ministry and Marie Curie Reintegration grant at the Institute of Biomedicine (IBUB) of the University of Barcelona (IBUB), the number one university in the current rankings in Spain and Catalonia. Her laboratory is located in the Barcelona Science Park, which is one of Europe’s leading ecosystems for research, technology transfer and innovation. Eva is a professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biomedicine and teaches in the Faculties of Biology and Pharmacy, in the Biology and Biochemistry Degrees of the Faculty of Biology (UB), and in the Master of Biotechnology (Faculty of Pharmacy, UB).