February 22, 2018.

I’m having a coffee, as I usually do every morning, on the terrace of the market bar, right on the corner of Maquinista and Baluarte. Sitting at one of the eight tables occupied since early morning by the retired people of this neighborhood—and we’re growing in number—I watch the streets that the garbage collectors have just watered, refreshing the atmosphere, and collecting the empty beer cans with which the night before’s botellón had littered the asphalt along with the vomit and dirt that the night visitors have left us as a witness that in Barcelona anything goes.

I had my Fuji X100 ready in case I needed to intervene—always from a distance, of course. Suddenly, I heard a scream behind me.

–Vicens, you haven’t heard. They found some bodies buried in front of my house. I’ve yelled at the police, but they’re not paying attention.

La Rosita used to shout a lot when he spoke, -like almost everyone in my neighborhood- for this reason they didn’t pay much attention to her.

“What do you want me to do? They must be two victims of a robbery, or who knows.

” “No. They’re skeletons. They were underground. Some excavators dug them up.”

Towards Balboa Street I meet my friend Joaquim, who somehow already knew about the discovery.

You already know? One of the workers from there told me.

We arrived at the place, Rosita disappears as if swallowed by the earth.

The site was closed off, it was inaccessible. I point the boss over the railing and get a glimpse of the work going on inside the site.

A pile of PVC pipes was piled up on a heap of earth on both sides of a trench a metre deep that a bulldozer had opened up with the intention of laying the pipes from the sewer in Calle Balboa to the one in Calle Ginebra.

Inside the building site, shouting at each other and threatening each other with their fists, workers from the construction company and technicians from the archaeology department of the Town Hall were disputing the execution of the work, some claiming the archaeological value of the discovery, and the others arguing that they had to keep to a timetable to complete the work for which they had been contracted. Meanwhile, outside in the street, the lorry with the cement mixer was constantly hovering with a noise that was only surpassed by the shouts of the driver who was saying that he had to pour the 10 tonnes of concrete that was already beginning to forge.

From that moment, taking advantage of the chaos, strung to the fence I was able to take a few photographs, and also talk to the archaeologists, shedding some light on the mystery of why those dozen skeletons had to be from the 17th century at least.

At first someone said it was a mass grave from the civil war, but it didn’t seem so from the position of the bodies. They were buried in a row next to each other without any parallelism with the streets or the buildings of the neighbourhood, the skulls pointing into the sea, and the feet to the houses forming a 45° angle without the technicians finding a logical explanation for this fact.

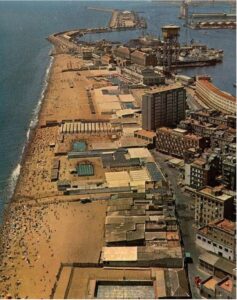

My theory was that when they were buried, Barceloneta did not exist, it was a huge sandpit, the land was outside the walls, and the bodies were deposited perfectly perpendicular to the sea.

The engineer Joan Martin Cermeño, in 1749, designed the streets of Barceloneta in a north-south / east-west direction. In this way he took advantage of the 4 prevailing winds in the area. -Tramontana, Llevant, Mitjorn and Ponent. The beach line crosses the neighbourhood diagonally, allowing both the north-south and east-west streets to lead to the beach.

After scrubbing the skeletons for hours with paintbrushes, the technicians vacuumed and labeled them, concluding that they were burials from the time of the Reapers’ Revolt, or the French siege of 1697.

It was clear that they were remains from the 17th century. Barcelona suffered an epidemic of the Black Death at that time. This would also justify burying them outside the walls to avoid further infection.

My conclusion was that those dozen or so unfortunates reached our coast aboard a ship with an epidemic of cholera, typhus or scurvy – a fairly common occurrence at that time – and they anchored, transferring the dead to land with the boats and burying them on the beach until they had passed quarantine and could disembark.

One way or another it worked out. Everyone, construction workers and town hall officials, kept receiving orders on their mobile phones, some not to stop the work, and others not to allow it to go ahead at all. The most curious thing was that both orders came from the same office.

At 2 p.m. sharp – like good civil servants – the archaeologists, hungry from the struggle, left for lunch, demonstrating that they would return the next day with more tools from the laboratory.

After they left, the trowels laid the pipes in a hurry, the concrete mixer poured all the concrete covering the PVC pipes, and the bulldozer filled it with the leftover earth, levelling the ground and burying the necropolis of the neighbourhood forever and ever.

When they arrived early in the morning, the scientists found a perfectly flat site with no sign that they had ever excavated there.

So they took the instruments, the Carbon 14, the paintbrushes and the hoover and went to lunch at the Jai-Ca bar, making time until lunchtime.

This is Barceloneta, a neighbourhood where all the big problems have easy solutions.