Before cemeteries were built outside the city, people were buried inside or around churches , depending on their social class: the upper classes were buried inside the churches, while the rest of the population was buried in graves or parish cemeteries, usually located around the church building.

This had been the case for many centuries

The prevailing belief was that the closer you were buried to the church, the closer you would be to God after death.A new shift in mentality occurred at the end of the 18th century due to the introduction of hygiene-related ideas from Northern Europe to Spain. These trends, the result of advances in medicine and science—with the discovery of viruses and bacteria—highlighted the need to protect the health of citizens by conducting studies on different urban spaces and population ecosystems, together with people’s customs and habits: what they drank, whether the water was of good quality, what they ate, their personal hygiene, the air they breathed, whether their homes were well ventilated, their working and resting hours, etc.

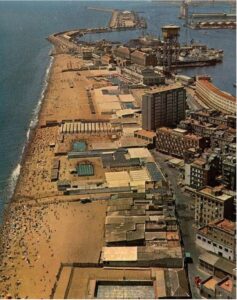

This led, in the future, to the design of more open cities with more green spaces, where there was an adequate sewerage system, buildings with ventilation and light, and the construction of possible sources of infection far away from cities. That is why parish cemeteries were the first spaces to be studied, because they were immediately considered spaces of decay, contamination, unsanitary conditions, and possible sources of transmission of dangerous epidemics for the inhabitants of walled cities. Remote and uninhabited places were sought, outside the walls, and often in places where there were polluting economic activities (such as slaughterhouses) or near landfills to be built. We do not think that this change in mentality was easy or quick. There was much reluctance and mistrust on the part of the parishioners, who did not look kindly on burying their dead far from the city and from ecclesiastical protection. It was a mentality that had been deeply rooted for centuries and that, over time, society would have no choice but to accept. The cemetery of the church of Sant Miquel del Port. There is no evidence that the church of San Miquel del Puerto had its own cemetery at the time of its construction. Even so, it is logical to think that, given that all the churches in the city had their own necropolis, when the church of Sant Miquel del Port was built in 1755, a space was designated for burying the to bury the residents who belonged to the parish. This space was probably located behind the church building, on the side facing Balboa Street, where the statue of the ‘Negro de la Riba’ is currently displayed, but some sources have suggested that there was something resembling a cemetery next to the church building, facing Maquinista Street. Unfortunately, there is no documentation to certify this with 100% certainty, nor have any remains been found from exhumations. Therefore, we cannot be sure that it existed, we can only guess. The first cemetery outside the city walls. In In 1775, the first attempt was made to build a cemetery outside the city walls of Barcelona. It was promoted by Bishop José Climent Avinent (1706-1781), one of the first advocates of hygienist trends in our country, who contributed to their dissemination. His struggle was based on transforming the urban landscape of the city to eliminate potentially dangerous spaces. The first record we have of the construction of a cemetery outside the city dates back to 1791. It was located on unpopulated land, very close to the beach, between the warehouses that served as a slaughterhouse, located where Balboa Street is now, and the old Lazaretto, more or less where the Hospital del Mar stands today. In those years, due to a yellow fever epidemic that struck the city, a temporary lazaretto was built on that land. This cemetery was used as an ossuary for the exhumed remains from other cemeteries and to bury the poor who died in the Hospital de Sant Pau i la Santa Creu. We know that in 1807 it was in a deplorable state, almost abandoned, possibly due to its ecclesiastical disassociation and its remote location, but we must not forget the reluctance of the urban population, which was still strongly influenced by religion and secular beliefs that made it difficult to normalise burials outside places of worship. In 1813, Napoleon’s troops destroyed this cemetery, of which no remains are left. There is little documentation mentioning this first cemetery outside the city walls, but it is curious that in Barceloneta, in its early days, there was a street named ‘Calle del Cementerio’ (Cemetery Street), which later, perhaps to contradict the previous name, was changed to ‘Calle Alegría’ (Joy Street) and is now called ‘Calle Andrea Dòria’. Given the location of the street, which runs from La Repla or the back of the church to the seafront promenade, its name could refer to the old cemetery of the parish of Sant Miquel del Port, or indicate the way to the cemetery built by Bishop Clemente. In 1818, Bishop Clemente’s theories were finally realised, and the construction of a cemetery outside the city was approved: the Poblenou Cemetery, known as the ‘Eastern Cemetery’, inaugurated the following year (1819) by his predecessor, Bishop Sitjar, and considered the first municipal cemetery located outside the city walls. (23 September 1801) – López Sopeña, Antonio.

The yellow fever of 1870

The city of Barcelona, and more specifically Barceloneta, suffered frequent epidemics of cholera, yellow fever and typhus in the 19th and 20th centuries. One of the most significant and well-documented was the yellow fever epidemic of 1870. At the end of August, rumours began to spread about a disease affecting some residents who had arrived on the ship Maria from Havana, which had docked in the port on 26 August. Thus, the epidemic began in the port and spread through the streets of Sant Telm and Pescadors, which at that time had no sewerage system and were full of old, overcrowded houses. One of the first conflicts that arose was where to bury the dead from the ships, which the mayor of the neighbourhood, Eduard Reig, opposed because of the health risk it could pose. Finally, it was decided to do so at night and with all possible protective measures to avoid contact with the population, in a secluded place such as the beach and covered with quicklime. As we can see, in extreme cases, improvised places were sought to keep the dead away from the rest of the citizens.

In September, given the magnitude of the outbreak, the Provincial Health Board decided to evacuate the neighbourhood. On 20 September, eight hundred poor residents of Barceloneta were transferred to the Montalegre health colony, located in the Cordillera de Marina, near Tiana, with capacity for two thousand people. On 22 September, the City Council and the Health Board ordered the forced evacuation of Barceloneta, forcing residents to hand over their keys to the mayor. On 5 October, entry into the neighbourhood was prohibited, and it was not until 17 November that the disinfection of streets and buildings began. Finally, on 1 December, the residents were able to return to their homes. Meanwhile, the residents who ended up in the Montalegre health colony were treated and cured, but some died and were buried in the colony’s own cemetery, which they called ‘the plague cemetery.’ Today, although it is abandoned, you can visit it and see a monument dedicated to the victims, with the inscription: “Colonia de Montalegre. The Barcelona City Council to the victims of yellow fever, 1870.” From the documentation consulted, we know that 76 residents of Barceloneta who died of yellow fever are buried in this cemetery, but due to the poor condition of the graves, there are no inscriptions, making it impossible to know where they were buried.

A secular burial

In the newspaper La Independencia on 2 December 1871, we find the following news item that refers to us in cemeteries. On 2 December 1871, Àngel Lucas Andreu, a resident of Barceloneta, interpreter of Swedish, Norwegian and Russian, married to Aurora Dols Boracino, and living at 34 Baluard Street, first floor, lost his eleven-month-old son, Plinio Lucas Dols. Àngel Lucas was a federal republican, a freethinker and a defender of atheism and reason, and he wanted to bury his son in the Poblenou cemetery, where he owned a title deed and had a certificate from the Municipal Court certifying this. Upon arrival, the presbytery of the Poblenou cemetery, Josep Fillol, demanded ecclesiastical authorisation in order to carry out the burial. When he refused to do so, he was denied use of his family tomb and the child was left in an unsanitary room known as the ‘Republicans and Freethinkers Section’, where he was buried. Àngel Lucas went to court to denounce what he considered a violation of his property rights, claiming: ‘And resolve the manner in which every citizen can exercise their legitimate property rights, a right that seems to be unknown to employees of the Catholic Church.’ This case was not unique: there were already other complaints against Josep Fillol, such as that of Josep Forest Prades, a carpenter, resident of Barceloneta and also a federal republican, who suffered a similar case with the burial of his newborn son a year earlier. Josep Forest had reported Mr Ahijado in May of the previous year for burying his son, a few months old, in the abortion cemetery, along with more than eight other children’s bodies, instead of in the family plot. Josep Forest finally managed to open the grave and bury his son in the family plot. The complaints against Ahijado were based on his disregard for property rights and his refusal to allow non-Catholic burials. These were two issues that were beginning to enter modern thinking and which came to prominence a century later.